Inside California’s Most Diverse Water Portfolio

A recap of “Food for Thought” Speakers Series: Santa Barbara’s Diverse Water System, Past & Present, which took place at the Neal Taylor Nature Center on September 14 from 2:00 pm – 4:00 pm.

During our Food for Thought program in September, presenter Jasmine Showers shared a story that might surprise most Santa Barbara residents: the city manages the most diverse water portfolio in the entire state of California. Even more remarkable? Santa Barbara uses the same amount of water today as it did in the late 1950s, despite its population growing dramatically since then.

As a Water Resources Analyst for the City of Santa Barbara, Showers has spent seven years working on the front lines of water management. Her presentation revealed the fascinating complexity behind the steps that lead to turning on your tap, something that many of us take for granted.

A City Built Around Water

Santa Barbara’s relationship with water infrastructure is nothing new. The story begins in 1806, when Franciscan friars built the first dam and aqueduct to support the mission. If you’ve ever walked above the Mission Rose Garden or driven toward Rocky Nook Park, you’ve passed remnants of this centuries-old system.

But as the city grew, so did the challenge of securing reliable water supplies. The solution? Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

Several Sources of Water

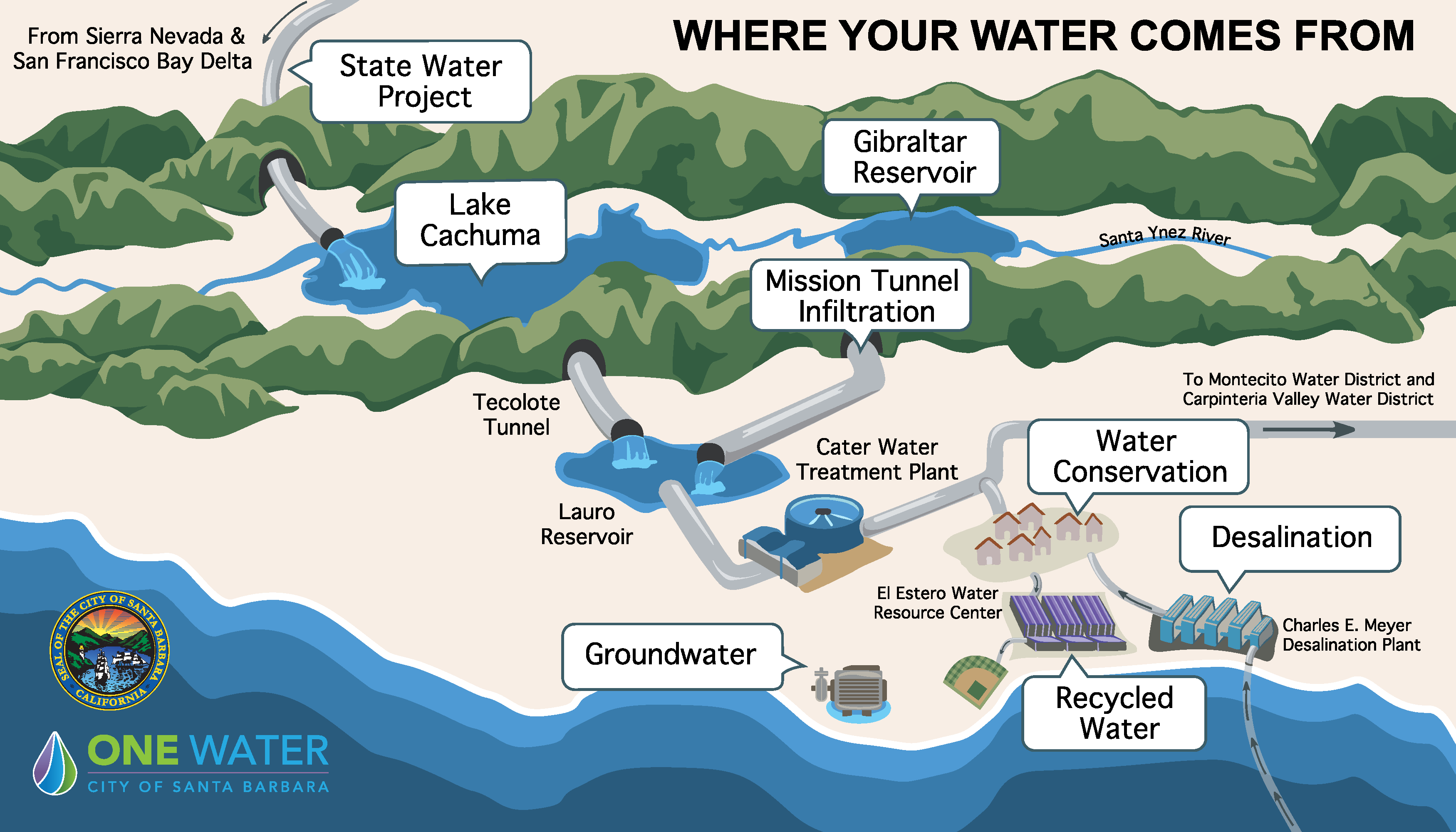

While most cities rely on one or two main water sources, Santa Barbara has developed a more diverse supply over the past century. It’s like having multiple different bank accounts so that if one runs low, you’ve got backups.

Lake Cachuma is a man-made reservoir built on the Santa Ynez River, with Bradbury Dam holding the water in place. The lake provides about 80% of what Santa Barbara city needs in a typical year, and also provides water for the rest of Santa Barbara county. Getting that water to Santa Barbara is an engineering marvel in itself. The Tecolote Tunnel, a six-mile passage carved straight through the Santa Ynez Mountains, brings lake water to the South Coast. When Showers shared tunnel construction photos from the 1950s, the dangers became clear: workers faced flooding, toxic gases, and extreme heat from geothermal pockets. Workers had to sit in “cooling cars” filled with water just to survive their shifts. Exhibits at the nature center also show these gruelling conditions, as well as the engineering marvel that is the Bradbury Dam and Tecolote Tunnel.

Gibraltar Reservoir was built along the Santa Ynez river over a century ago with impressive wooden scaffolding that looks like something from an engineering textbook come to life. The reservoir still supplies about a third of Santa Barbara’s water, though it faces a problem common to mountain reservoirs: sedimentation. Every wildfire followed by heavy rain sends debris flowing into the lake, gradually reducing its capacity. The good news? The massive rains of 2023-2024 actually flushed some of that sediment out. Gibraltar reservoir is upstream from Cachuma Lake and acts as a sediment trap, contributing to a relatively low sedimentation rate in Santa Barbara’s main reservoir downstream. The water from Gibraltar reservoir reaches the south coast through Mission Tunnel.

The State Water Project connects Santa Barbara to a massive 705-mile network of aqueducts and reservoirs stretching from Northern California. It’s an insurance policy more than a primary source, and it comes with complexity: this year, despite plenty of water in the system, Santa Barbara received only 50% of its allocation due to competing demands and environmental protections. The state water project feeds water into Cachuma Lake for storage, and if Cachuma Lake spills, Santa Barbara loses its allocation of that water.

The desalination plant might be the city’s most high-tech solution. Originally built in the 1990s, the city smartly kept its permit active even after deciding not to use it initially. That foresight paid off when drought struck and the plant was reactivated in 2017. The plant can provide up to 30% of the city’s water if needed by pulling seawater from 40 feet down. The purification process is so thorough that minerals have to be added back in, otherwise the ultra-clean water would damage pipes!

Groundwater basins beneath the city act like underground savings accounts. There are seven production wells, mostly in the downtown area. Technically they can store about a year’s worth of water for Santa Barbara (10,500 acre feet), but only 12% of that (1200 acre feet) can be sustainably pumped each year, allowing the aquifer to recharge. The city hasn’t tapped them since 2023, preserving this critical resource for when it’s truly needed.

Recycled water serves golf courses, parks, and landscaping throughout the city, anywhere you see purple pipes. This system keeps drinking water in the tap where it belongs, rather than being used to water lawns. The plants apparently love it; the extra nutrients in treated wastewater help the vegetation thrive.

Water conservation is also considered a part of the water supply portfolio, which has allowed Santa Barbara’s total water use to remain the same as it was in the late 1950s despite population increase.

The Conservation Success Story

Santa Barbara’s water production peaked in 1984. Then came the brutal drought of the late 1980s, forcing residents to cut back dramatically. When rains returned, however, water use never bounced back to previous levels because of people’s continued conservation efforts.

New landscaping rules, implemented in 2007, require water-wise plants for both commercial and residential projects, which makes a huge difference in saving water. The city offers rebates for replacing thirsty lawns and delivers free mulch to slow down evaporation. And in 2024, the city launched automated meter reading, which allows residents to track usage and detect wasteful leaks hour-by-hour instead of monthly on ther bill. 57% of customers have signed up, a remarkable adoption rate that shows Santa Barbarans take water conservation seriously.

The Reality of California Rainfall

One audience member asked the question many wonder about: Can we predict when the next drought will hit?

Showers pulled up a rainfall chart spanning from 1897 to 2023, and the answer became obvious: not really. California doesn’t experience predictable cycles. Instead, rainfall follows what looks like a staircase; long, dry plateaus punctuated by sudden drops and occasional dramatic spikes. The February 2023 storms that caused Lake Cachuma to overflow provided spectacular photos of water spilling over the dam, but such abundance is impossible to forecast.

Climate change is making this unpredictability worse, turning water planning into an increasingly complex game of chess.

The Challenges Ahead

Managing several different water sources means juggling different sets of challenges.

Gibraltar Reservoir continues filling with sediment, and despite various proposals to clear out sediment, the remote mountain location makes dredging economically impractical. The Mission Tunnel, completed in 1911, still carries water reliably but its infrastructure is over a century old.

Water allocation involves complex negotiations between federal authorities, state agencies, water districts, and environmental requirements. Endangered species protections sometimes limit how much water can be used, even when reservoirs are full. Storing water in distant San Luis Reservoir provides backup supplies, but if that reservoir spills, stored water is lost—as happened in 2023 when the city forfeited 16,000 acre feet.

Perhaps the biggest question during the Q&A session came from someone asking about “toilet to tap,” the practice of treating wastewater to drinking water standards that Orange County has pioneered. Showers noted that while the technology exists and the city’s recycled wastewater used on landscapes already receives the highest level of treatment, California is still finalizing regulations for direct potable reuse. It’s a cultural hurdle as much as a technical and political one.

Residential vs. Commercial Water Use

During her presentation, Showers shared a breakdown that might surprise some residents. Residential use accounts for about two-thirds of total water consumption. Commercial and industrial use makes up about a fifth, with irrigation (including that purple-pipe recycled water) accounting for the rest. “A lot of people maybe think that there’s more businesses and commercial use than there actually is,” said Jasmine, showing that household conservation efforts really do make a difference. Every efficient toilet, every native plant garden, every shortened shower adds up across thousands of homes.

What Makes Santa Barbara Special

By the end of the presentation, what emerged was a portrait of a community that has learned to live within its means, an incredible accomplishment in water-stressed California.

The diversity of Santa Barbara’s water sources means the city isn’t as vulnerable if one water source fails. When Lake Cachuma runs low, the desalination plant can ramp up. When surface water is abundant, groundwater basins can be preserved. During droughts, conservation measures kick in with public support because residents understand the reality of the situation.

This wasn’t built overnight. It took over a century of infrastructure investment, some hard lessons learned during droughts, and a community willing to change habits. Each decision built toward the resilience the city enjoys today.

A Model for the Future

As California faces an increasingly uncertain climate future, Santa Barbara’s approach offers lessons for other communities. Diversity beats dependence. Conservation isn’t sacrifice—it’s smart management. And perhaps most importantly, water challenges require both technological solutions and community commitment.

Because the more we understand where our water comes from and how much effort goes into delivering it reliably, the better equipped we are to be partners in preserving this precious resource.

We would like to thank Jasmine Showers for her work and her presentation, as well as all of the government and state workers who make sure that water comes out of the tap every day. The Neal Taylor Nature Center’s “Food for Thought” will continue to bring stories like these to the public, and we hope you will join us for the next one!

The Neal Taylor Nature Center at Cachuma Lake hosts the “Food for Thought” Speaker Series regularly, featuring expert presentations on topics related to our local area. Visit https://www.clnaturecenter.org/calendar for upcoming events and programs.